Dhall & Nash’s Focus On:

Fact, Fiction or Fantasy

Vinous MythBusters: Debunking Common Wine Myths

Happily for us at Dhall & Nash, wine is everywhere these days, but so too are misconceptions about our favourite fermented friend.

There is absolutely nothing wrong with having favourite grapes, producers, or wine regions. But limiting yourself to only those wines you know you like closes the door on the vast, unexplored territory occupied by all the wines you’ve learned little to nothing about. Unwittingly, your hidden wine prejudices may be fencing you in!

Certain common misconceptions about wine can become unquestioned truths. And once they harden into beliefs, they inevitably put-up barriers around anyone’s ability to expand their wine knowledge and enter the playful and immensely pleasurable realm of tasting new wines.

We want to Focus On debunking a few widespread wine myths so that you can impress your friends, fend off irritating wine snobs, and most importantly open your mind and palate to some fabulicious fun wines.

This can apply to even a seasoned enthusiast or if you’re just getting into this whole wine thing, there are quite a few myths nearly every wine drinker mistakenly believes (Oops! Guilty as charged).

Here are a few myths we’ve busted to help dispel some misconceptions we’ve all come across at one point or another in our wine adventures:

All Chardonnays Are Too Oaky

This old chestnut – the ABC Club – Anything But Chardonnay club. Really darling? Really? All we can say is – never let fashion dictate what you enjoy. Be a tastemaker, not a slave to fashion.

Anything But Chardonnay was a movement that stemmed from the dominance of this style in the Californian market back in the 1980s, and in NZ we followed suit – throw more expensive oak at it meant a more expensive chardy but not necessarily a finer crafted chardy. Just like over-salting your food, this was all wrong. But times and winemaking styles have well and truly changed yet a lot of people still believe, mistakenly, that all chardonnay is big and over-oaked.

Oak is really, really amazing and when used judiciously, adds beautiful texture and complex, enticing character to wine, though it’s easy to overdo. Thankfully it’s all about the pursuit of balance in wines nowadays. Winemakers know it. And the wine buying public needs to know it by now. Embrace a tantalisingly brilliantly balanced Chardy like Easthope Family Winegrowers Skeetfield Chardonnay or Domaine Testut Chablis.

All Rieslings Are Sweet

False. In fact, nothing could be further from the truth. Riesling, amazingly, is one heck of a versatile grape variety. It can be made into ice wine from frozen grapes on the vine, it can be made late harvest if the conditions are just right, AND in more cases than not, it can be made bone dry!

If you’re a fan of tart, crisp wines and Riesling hasn’t been rotated into your repertoire, you are missing out. Dry Rieslings have a lip-smacking acidity that is mouth-watering and totally moreish.

Rieslings are scintillating, pure, powerful, haunting, dry, and some of the most ethereal wines ever made. Period. No need to say more – time for you to try: Schloss Lieser Niederberg Helden Riesling Trocken GG (375mls Half bottles also available)

Sulphites Are the Cause of All Wine Headaches

Nope, not even close to true. An entire bottle of wine contains less sulphite than a couple of dried apricots; and believe it or not, white wine typically has more sulphite than red.

We may need to do a deep dive on this myth – here goes: Sulphites are sulphur compounds that occur naturally in the grapes and hops used to make wine and beer. They prevent the growth of the bacteria that make the drink go cloudy, literally turning the alcohol into vinegar. Most wines and beers have extra sulphites added as a preservative and some people claim that this can cause headaches. Drinking sulphite-free wine for the sake of not having a headache is totally an urban wine myth.

There are several things that are more likely to contribute to wine headaches that are unique to each person: alcohol level, sugar content, not drinking enough water and other chemicals/additives can all cause headaches (see more below).

Next time you pour a second or third glass of wine for the evening, check the wine bottle label first, you may be surprised to see that your Barossa Shiraz is 16% alcohol!

There Are More Sulphites in Red Wine

Some people say they can drink white wine with no ill effects but not red.

While it’s true reds possess more natural sulphites, white wines require the addition of considerably higher levels of sulphur dioxide in order to maintain freshness. For the record, white wines, particularly sweet whites, contain up to 10 times the level of sulphites as reds.

So, what is it about red wines that cause so many allergic reactions/headaches? There are actually several factors that have been studied.

The first and most common are histamines. Histamines are found in nature in many forms including plant matter, i.e., grapes, and cause those susceptible to suffer from sinus issues. Since pollen and other goodies are trapped on the surface of the grape skins — and only red wines come in contact with the skins, it stands that those who are sensitive to histamines will be affected when they drink red wine.

Histamines can be up to 200 percent higher in reds than in whites. There is a home remedy or old wives’ tale that recommends drinking a cup of black tea before consuming red wine. The compound quercetin found in black tea has been thought to inhibit the flushing effects of histamines, but this has not been studied extensively. Probably a more effective method is to take an over-the-counter antihistamine. But make sure you choose the non-drowsy variety, or you may fall asleep in the middle of your toast to good red wine.

The second factor is tannin. Tannins in red wine can cause small levels of serotonin release in the brain, affecting those prone to migraines. But several Harvard studies have shown that those not prone to migraines did not get headaches from increased levels of tannin.

Prostaglandins are the third factor studied. Prostaglandins are substances that cause pain and swelling. When combined with the dehydrating properties of alcohol, they’ve been thoerised to increase the likelihood of headaches when drinking red wine. The biochemistry behind this one is quite a bit more detailed, so we won’t bore you with the details, but prostaglandins are everywhere. If you are particularly sensitive, then taking Ibuprofen, which is a prostaglandin inhibitor, may be helpful.

The fourth factor has not been studied, at least in any respectable research setting, but it is a theory amongst us in the trade… Cheap “Industrial Level” Wine! We are convinced that poorly-made wine contains more unbalanced bacteria, junk, stems, detritus, bugs and who-only-knows-what. It’s no wonder people get headaches from it. In order to make quality wine, a winemaker has to invest in quality production from the grape to your glass. There’s no way that a $8 bottle of wine can be made “well”.

Just sayin’!

All Wines Get Better With Age

While the majority of us would love nothing more than to enjoy a bottle of 1996 Château Margaux, the truth is that not all wines are meant to be enjoyed at a later date. In fact, about 90% of wines are made to be consumed within the first 3-5 years of their life. So, unless you’re buying special bottles for your cellar, go ahead and crack open that bottle of wine sitting in your closet, it’s probably really ready to drink!

Wine "Legs" Are Evidence of Wine Quality

Wrong! Legs are the streaks down the side of a wine glass. They largely are a product of the alcohol level. Thicker, slower legs merely indicate a higher alcohol level, but that is separate and quite apart from quality.

“Never judge a book by its cover” – this could be just as aptly applied to rose’ – “Never judge a rose’ by its colour”

– Dhall & Nash’s Blogger Mama Sonja

The Darker the Rosé the Sweeter it Will Be

Codswallop! Admittedly there is a big issue that wine drinkers everywhere confront: decoding rosé’s colour, which can range from the palest blush, to full-bloom azalea. The first question most people have upon seeing a darker rosé is: Will this wine be too sweet? In short, the answer is most likely no.

The reality is that a quality rosé, even if it is dark, will contain neither added nor residual sugar. A rosé’s colour can, however, give you some important information on how it was made, and how it will taste; in general, lighter rosés are bright and crisp, darker rosés have more fruit, texture, and body. It all depends on skin and time.

One of the main factors in a wine’s colour is skin contact. This refers to the amount of time that winemakers allow the juice to remain on the red skins before removing them—it can be as little as a few hours, or as much as several days, depending on the producer and regional style.

Perhaps the best example of the differences between lighter and darker rosés can be found in Southern France, where pale pink Provençal rosé and deep ruby Tavel wines from the Rhône Valley are produced with special care and pride. These regions are known for their rosé wines, where they even plant grapes specifically for rosé, which is not the case everywhere.

In a lot of places, people make rosé as a by-product of their red wine production – referring to the saignée technique in which winemakers briefly macerate red grapes with the skins, “bleed” some juice off for rosé, and then use the more concentrated juice to make a red wine.

Because of Tavel and Provence’s focus on turning out top-quality rosé, they’re harvesting the grape when it’s at the perfect balance of fruit, acidity and ripeness to make a beautiful, balanced rosé, with just enough richness and acidity to satisfy the thirst that a great meal generates.

In Bandol, a sub-appellation of Provence renowned for top notch rosé, they make their rosé with a heavy dose of the grape Mourvèdre, which lends a slightly darker hue to the wine. By law Bandol rosé must be made with between 20 to 95 percent Mourvèdre. Mourvèdre makes a rich, dark, super tannic red wine. In rosé, Mourvèdre provides a rich texture, but also a razor-like acidity which can make for a bright, crisp, refreshing rosé.

Climate also plays into such varietal characteristics; grapes growing in warmer climates tend to have thicker skins, so the rosés will be darker like in Hawkes Bay. Because of the high proportion of Mourvèdre in Bandol rosé, it can be slightly darker than the broader Côtes de Provence rosé, which can include a wider variety of grapes from all over the appellation.

All of these factors affect a rosé’s colour, but it comes down to a winemaker exercising his or her judiciousness—and expressing a regional style—it’s about determining the amount of time that grapes sit on their skins. In Tavel, winemakers typically let the juice sit on the skins for more time, up to 48 hours, which gives the wine more tannin and structure, as well as a more intense fruit profile. This style of rosé, known as rosé d’assiette—meaning “rosé for the plate” (as in for a meal)—displays a more savoury quality and concentrated fruit.

Pale Provençal rosé, meanwhile, has a flavour profile somewhat closer to white wine. It’s more floral, with gardenia and white blossoms, bright high-toned fruit, and often more delicate flavours. The juice is frequently removed from the skins within the first 12 hours during maceration.

Ultimately, why not forget about the sweetness or colour question, and instead get excited about the range of rosé wines out there – ask your sommelier, wine shop assistant or us here at D&N what different styles are available to suit the occasion – richer, fuller rosé, or something bright, light, and easy drinking.

“We’ve all been conditioned to think that the best rosés come from the most recent vintage possible. Not so!”

– Ian Cauble, Master Sommelier

You Should Only Drink the Latest Vintage of Rosé

Why is this soooo not true? Because you can enjoy other vintages too, and not just the latest.

It’s true that over time, the colour drifts from bright pink to more of a salmon-pink tinge and aromatic expression gradually displays spicy, toasty, floral or ripe fruit notes in addition to the yellow or white fruit aromas, citrus, and tropical fruits. But the wines are not fading, they are broadening their spectrum. The slightly older vintage of a rosé wine is still gratifying and continues to display its iconic style but will appeal to inquisitive consumers who keep an open mind when it comes to new profiles.

Rosé is for Summer Drinking Only

Admittedly, rosé consumption is higher when the sun shines, but there are so many styles of rosé that are suitable for all-year round drinking, it’s just a matter of open-mindedly choosing a weighty ‘winter’ rosé that pairs perfectly with the right food or moment.

Rosé wine’s versatility is an advantage when it comes to the dinner table. They stand up flawlessly to all types of cuisine from Mediterranean, to Indian and to Asian dishes. For foods with stronger flavours—like grilled or smoked seafood—we’d recommend a bottle of the more complex weightier Château Gassier Cuveé 946. Whereas for something lighter, like sushi or poached salmon, we’d lean towards the lighter style of pinot noir rosé, like the Folium. A classic Provençal style rosé like Château Gassier Esprit is also great for drinking on its own, as an aperitif.

Everybody's Tired of Drinking the Same Old Thing

People are ready to see that there's different stuff out there. Welcome to the world of Natural Wines and, of course, its myths.

Think natural wine is nothing more than a trendy hipster magnet? Think again. A minimalist approach to winemaking is moving into the mainstream—though not without its misconceptions, naturally. We want to crush the myths and embrace bottles that aren’t made from grapes doused with chemicals or otherwise overly manufactured and manipulated. Less really can be more. Here are some myths of the natural wine movement, along with some D&N bottles to make you a believer.

Natural Wine Is Just a Fad

Though it’s a buzzy category of late, natural wine has actually been around for thousands of years, since the first thirsty people decided to throw crushed grapes into a vat and see what happened. “The Romans weren’t spraying Roundup on their vines, and the Cistercian monks of Burgundy weren’t buying yeast to inoculate their fermentation,” says Danny Kuehner, the Head Sommelier at Madison in San Diego. “This grassroots movement among wine enthusiasts will only continue to grow.” Just as organic produce, free-range poultry and whole foods have become part of our permanent culinary lexicon, natural wine is here to stay.

Natural Wines Don’t Age Well

News flash: The vast majority of all wines produced in the world are meant to be consumed within a few years. And let’s face it—most wines rarely make it longer than the trip from the grocery store to our glasses. Age-worthy wines, no matter how they’re made, generally have high acidity and/or tannins, both of which act as preservatives. Making a blanket statement about how long natural wines are going to hold up is silly, says Sommelier Sebastian Zutant. “Ask the folks at La Stoppa why their current release of their high-end Barbera is 2011; it’s singing and could use some more time,” he says. “Anyone making this point simply hasn’t tried older natural wines. They age.” D&N bottle to try: La Stoppa Riostoppa 2014

Natural Wines Taste Funky

OK, this myth actually has some legitimacy. But is funkiness in wine a bad thing? We say no. A tiny level of brettanomyces—that is, the strain of yeast that gives some wines a whiff of barnyard or saddle leather—or the doughy notes gleaned from leaving dead yeast cells in the bottle rather than filtering them out can elevate a wine. Add another layer of complexity. Natural wines have a broader range of acceptable flavours. But within that broad swath are also all of the same flavours of commercial wines. Just like some sour beers might not be your jam, others may be the mouth-watering, tart, and tangy brews you’re craving. The right natural wine to pique your palate is out there waiting to be uncorked. D&N bottle to try: De Martino Viejas Tinajas Muscat 2018 Or De Martino Cinsault – fermented in traditional underground clay pots

Dr Jo Brysnska, Wine Writer expounds that it is a “…great time to enjoy that newly popular style that sits on its own sensory threshold, the chilled red.”

Red Wines Should NEVER Be Chilled

While it is true that most reds should be served at room temperature (more on this later) there are a few exceptions.

Traditionally there is one style that is always chilled: Beaujolais Nouveau. This wine is made from the very first grapes harvested every year in Beaujolais France and goes through carbonic maceration – giving it a tutti-fruity flavour. Now, thanks in part to the Natural Wine movement, there are decidedly many lighter and more juicy-licious red wine styles made in such a way that they drink much better with a bit of a chill on them.

With heavier reds generally, it is a bit trickier, depending on the age and texture of the wine. Ideally, a bottle should be slightly cool to the touch. Modern room temperature can often leave a good red seeming flabby or fatiguing. A slight chill is bracing to the wine. Tannic wines served too cold can seem tough and unpleasant. If a bottle seems too warm, 15 minutes in the fridge — or, at a restaurant, 10 minutes in an ice bucket — can work wonders. Give it a go. D & N Bottle to chill – Nat Cool Drink Me Vermelho OR Easthope Family Winegrowers Gamay Noir.

But remember – serving some white wines too cold will strip them of all flavour and conversely, mediocre whites ought to be served ice-cold, the temperature masks any flaws.

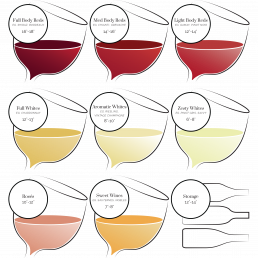

Here’s our suggested temperature guide to serving different wine types:

Full Reds (Shiraz, Bordeaux, etc.) – 16°-18°C

Medium Reds (Pinot Noir, Chianti) – 14°-16°C

Light Reds (Beaujolais, some gamay noir) – 12°-14°C

Full Whites (Grand-Cru Burgundy, Chardonnay, Roussanne) – 12°-13°C

Rosé Wine – 10°-12°C

Complex Aromatic Whites (Riesling, Gewürztraminer, Vintage Champagne) – 8°-10°C

Sweet Wines – 7°-8°C

Aromatic zesty wines (Sauvignon Blanc, Pinot Gris/Grigio, NV Champagne) – 6°-8°C

The ideal temperature to store wine – so-called ‘cellar temperature’ is between 12°-14°C and the most important thing is that the temperature is steady with no big fluctuations.

The magic of wine is that it is complex, beguiling, exciting and interesting. It also tastes pretty darn good too, which we’d argue is the most important thing of all! There’s plenty of myths to trip up the unwary though, and many ‘facts’ taken as truth that are easy to avoid. We hope this blog has shed a smidgeon of light on these vinous myths and opened the doors to try something deliciously drool-worthy and new too. Enjoy! ☺

You Should Always Decant an Old Wine

Actually, in some cases you really shouldn’t – this is not a hard and fast rule. Yes, sometimes there may be sediment in the bottle to avoid, but some very old wines are also very fragile and might be magnificent for the first 15 minutes after decanting, and then rather tired after 30 minutes. If in doubt, pour a small tasting sample, taste it, and taste it again in half an hour or so. Make your choice then. If still in doubt check online wine reviews first. ☺

“Bottle Shock” is Just a Wine Snob’s Term When Their Expensive Wine Doesn’t “Measure Up”

This has validity. Wine is a living thing, and when it gets jostled and disturbed by travel — be it in a container ship or truck or car trunk — it can respond negatively, much the way you feel with jet lag. The result can be a loss of aroma and flavour, which is what happened to the legendary white wine from California in the Judgment of Paris.

Fortunately, wine heals with a little R&R — and that healing allowed the Château Montelena Chardonnay to win the 1976 Judgment of Paris and put American wines on the world stage. It is why the movie about this event is titled “Bottle Shock”.

Next is an oldie, but a goodie…

A Teaspoon in the Neck of Your Opened Bottle of Champagne, Prosecco or Beer Keeps Them Fizzy for Longer

Let’s start with the supposed science. The teaspoon is said to act as a temperature regulator, as it absorbs the warm air from the neck of the bottle. The air around the teaspoon now gets colder and as cold air is denser than warmer air, the teaspoon creates a kind of air stopper, preventing the gas from escaping. The bottle with no teaspoon has no ‘air plug’ so the gas has an open route to escape. So, the cold temperature retains more carbon dioxide, and a teaspoon holds some metallic merit, at least overnight.

Here’s the actual testing. In 1994, the spoon trick was put to the test by Prof Richard Zare, a chemistry professor at Stanford University, California. He asked a panel of eight amateur tasters to judge the fizziness of champagne poured from 10 bottles. Some had just been opened, while others had been left for 26 hours with either nothing, or a spoon made of either silver or stainless steel in their necks. The judges weren’t told how each bottle had been treated. The conclusion: none of the spoons had any real impact on the fizziness – a finding later confirmed by the professional association of champagne producers in France.

So, what’s the best thing to do? Get yourself a stopper and keep the drink in the fridge. Carbon dioxide gas, which gives champagne its fizz, is more soluble in colder liquid, so the bubbly will better retain its sparkle. Or better yet – buy D&N’s CORAVIN Sparkling Wine Preservation System.

The magic of wine is that it is complex, beguiling, exciting and interesting. It also tastes pretty darn good too, which we’d argue is the most important thing of all!

There’s plenty of myths to trip up the unwary though, and many ‘facts’ taken as truth that are easy to avoid. We hope this blog has shed a smidgeon of light on these vinous myths and opened the doors to try something deliciously drool-worthy and new too.

Enjoy! ☺

2020 Easthope Family Winegrowers Skeetfield Vineyard Chardonnay, Hawke’s Bay, New Zealand

“The unique site that is the Skeetfield vineyard in Hawke’s Bay captures a sense of place and time in its chardonnay fruit showcasing scents of new season peach then quince, ripe grapefruit, there’s no mistaking the mineral layer enhanced with a wild white flowers suggestion. Delicious, weighty, vibrant and fresh on the palate with flavours that mirror the bouquet, there’s a youthful and refreshing acid line with a touch of salinity to it, fine tannins and balanced reserved use of oak. An excellent example, well made, lengthy and delicious! Best drinking from 2021 through 2029.”

95 points – Cameron Douglas

2020 Château Gassier Esprit Gassier IGP Méditerraneé Rosé, Provence, France

Shades of pale peach. A delicate nose with white and yellow fruit aromas. On the palate, a mineral wine with a beautiful freshness and a touch of acidity on the finish. A sumptuous and elegant rosé that will transport you to a magical corner of the Mediterranean sea. Majority Grenache, Syrah, Cinsault.

2018 De Martino Viejas Tinajas Muscat, Itata Valley, Chile

“Like many of the wines, this is the finest bottling for this cuvée in an almost-perfect vintage. This has moderate alcohol (12.8%) and very high acidity, something quite unusual for the variety, and it gives a lively character to the palate with citrus freshness. It has varietal notes, but more than that, it is very clean, complex and floral, with notes of orange peel. It’s a lot cleaner than the initial vintages, without any rusticity, and is focused and bone dry.”

93 points – Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate

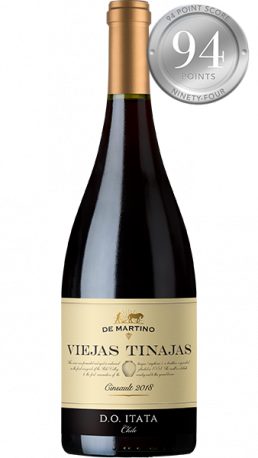

2018 De Martino Viejas Tinajas Cinsault, Itata Valley, Chile

“This is precise, expressive and fresh, with a wild character, very different from the other Cinsaults. It has a brothy, meaty touch on the palate that makes it very tasty. Clean and precise, with very good grip, 2018 has to be the finest vintage to date for this wine.”

94 points – Robert Parker’s Wine Advocate